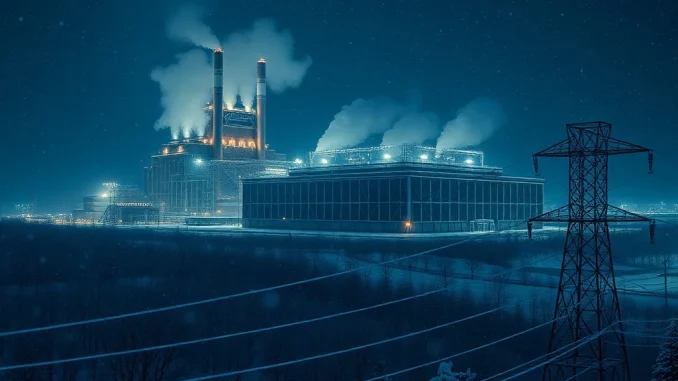

United States, February 2025: A powerful winter storm sweeping across the United States has triggered a remarkable and strategic pivot within the cryptocurrency industry. Rather than powering their energy-intensive computers to mine Bitcoin, numerous mining operations have chosen to shut down entirely, selling their pre-purchased electricity back to the strained power grid. This decisive move, driven by soaring energy prices during peak demand, has reportedly generated profit margins up to 150% higher than standard mining activities, according to industry analysis. The consequential drop in global Bitcoin hashrate to a seven-month low underscores the profound and immediate impact of this real-world event on digital asset infrastructure.

Bitcoin Miners Transform from Power Consumers to Critical Suppliers

The core business of Bitcoin mining involves solving complex mathematical problems to validate transactions and secure the network, a process that consumes vast amounts of electricity. Miners typically secure long-term, fixed-rate power contracts to manage this, their largest operational cost. However, during extreme weather events like the recent continental winter storm, residential and commercial demand for heating spikes dramatically. This surge creates a supply crunch, causing wholesale electricity prices in certain regional grids to skyrocket, sometimes by several hundred percent. Astute mining operators recognized this arbitrage opportunity: the value of the electricity they held the rights to suddenly far exceeded the value of the Bitcoin they could produce with it.

Scott Norris, Chief Mining Officer at Omnes, a firm specializing in Bitcoin hashrate tokenization, provided clear figures to DL News. “During peak demand periods, miners could sell power back to the grid for around 20 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh),” Norris explained. “Conversely, the revenue from mining at current Bitcoin prices and network difficulty equates to roughly eight cents per kWh.” This 150% premium creates a powerful financial incentive to temporarily cease operations. This activity, known as demand response, is not entirely new but represents a maturation of the mining industry’s integration with traditional energy markets.

The Mechanics of the Grid Power Play and Its Market Impact

This strategic shift from mining to energy reselling is facilitated by pre-arranged agreements with local utilities or grid operators. Many modern, large-scale mining facilities are built with this flexibility in mind, allowing them to act as a virtual power plant (VPP). When the grid operator signals a critical need—often through a high-price alert—these miners can power down their ASIC machines within minutes and feed their allocated power back into the system. This provides three key benefits: it stabilizes the grid for consumers, generates extraordinary short-term revenue for miners, and demonstrates the potential value of flexible industrial load.

The immediate effect on the Bitcoin network was quantifiable and significant. The global hashrate—a measure of the total computational power dedicated to mining—plummeted to approximately 663 exahashes per second (EH/s), its lowest point in seven months. A lower hashrate means less competition among the remaining active miners, temporarily increasing their profitability until the difficulty adjustment occurs. Meanwhile, the financial markets reacted positively to the news of enhanced miner economics. Publicly traded mining companies like TeraWulf and Iren saw their stock prices surge 15% and 18%, respectively, over a five-day period, as investors priced in the new revenue potential from these grid-balancing acts.

A Historical Context: Energy Markets and Crypto’s Evolving Role

The relationship between Bitcoin mining and energy grids has been a topic of intense debate for years, often focusing on environmental concerns. This recent event, however, highlights a more nuanced and symbiotic potential. It mirrors demand-response programs used by aluminum smelters or data centers for decades. The unique aspect of Bitcoin mining is its geographic agnosticism and interruptibility; a mining rig can be turned off and on with minimal operational consequence, unlike a factory production line. This episode provides a concrete case study for policymakers and energy analysts, showcasing how cryptocurrency infrastructure can contribute to grid resilience during crises, rather than merely being a baseload consumer.

Previous winter storms and heatwaves have seen similar, though less widespread, behavior from miners. The scale and profitability reported during this 2025 event, however, suggest the practice is becoming more systematized and financially material. It also raises questions about the long-term implications for network security if large portions of the hashrate become regularly interruptible based on external energy market conditions.

Conclusion: A New Paradigm for Cryptocurrency Infrastructure

The dramatic decision by US Bitcoin miners to halt operations and sell electricity during the winter storm marks a significant moment for the industry. It moves the conversation beyond simple energy consumption to one of dynamic energy management and market participation. The stunning 150% profit surge available through this mechanism reveals a powerful secondary revenue stream that can subsidize and stabilize mining operations during normal periods. As extreme weather events potentially become more frequent, the ability of large, flexible loads like Bitcoin mining farms to support grid stability will likely attract greater attention from both energy regulators and financial investors, cementing a more integrated role for crypto infrastructure within the broader energy economy.

FAQs

Q1: How do Bitcoin miners sell electricity back to the grid?

Miners typically have agreements with utility companies or grid operators that allow them to participate in demand response programs. When grid demand is critically high, they receive a signal and can quickly power down their mining rigs. The power they had contracted to use is then freed up and effectively “sold” back to the grid at the prevailing high spot market price.

Q2: Why did the Bitcoin hashrate drop so significantly?

The hashrate dropped because a substantial number of mining machines in the United States—a major global hub for mining—were turned off. With less total computational power competing to solve blocks, the network’s overall hashrate measurement naturally falls. This is a direct, real-time reflection of mining activity ceasing.

Q3: Does this mean Bitcoin mining is bad for the grid?

This event illustrates the opposite in a crisis scenario. While mining is a constant energy consumer under normal conditions, its unique flexibility allows it to become a grid-stabilizing asset during peak demand. By powering down, miners reduce strain on the grid, making more power available for essential heating and other critical needs.

Q4: Will this affect Bitcoin transaction times or fees?

Potentially, but the effect is usually minor and temporary. A lower hashrate means blocks may be found slightly slower until the next difficulty adjustment (which occurs roughly every two weeks). However, the network continues to function. Any impact on transaction fees would depend on whether the reduction in mining power coincides with a period of high transaction volume on the blockchain.

Q5: Is this practice sustainable for mining companies long-term?

As a supplemental revenue stream, it is highly sustainable and attractive. It provides a hedge against volatile Bitcoin prices and periods of low mining profitability. For mining operations located in regions with volatile energy markets or extreme weather, building this demand-response capability is becoming a standard part of the business model to ensure economic resilience.